I have just finished reading The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned from the Market's Perfect Storm, written by Robert Bruner and Sean Carr in 2007. It is extraordinarily well documented step by step study of one of the worst bank panics and stock market crashes in modern times. (The broad stock market declined 37% from peak to trough in less than 15 months.)

I have just finished reading The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned from the Market's Perfect Storm, written by Robert Bruner and Sean Carr in 2007. It is extraordinarily well documented step by step study of one of the worst bank panics and stock market crashes in modern times. (The broad stock market declined 37% from peak to trough in less than 15 months.)Here is an extended quote from the author's closing remarks.

"Why do markets crash and bank panics occur? Any single case study, such as the one we have presented here, is subject to a range of interpretations, and we encourage the reader to draw one's own conclusions from the foregoing narrative.

Yet we think that the story of the panic and crash of 1907 inspires consideration that major financial crises can be the result of a convergence of certain unique forces - the forces of the market's perfect storm - that cause investors and depositors to act with alarm.

The recounting of the events of 1907 suggests that the storm gathers as follows.

It begins with a highly complex financial system, whose very complexity makes it difficult for anyone to know what might be going wrong; by definition, the multiple parts of the financial system are linked, which means that trouble in one institution, city, or region can travel easily and quickly to others.

Buoyant growth in the economy makes the financials system more fragile, in part due to the demand for capital and in part due to the tendency of some institutions to take on more risk than is prudent.

Leaders in government and the financials sector implement policies that advertently or inadvertently increase the exposure to risk of crisis.

An economic shock hits the financials system. The mood of the market swings from optimism to pessimism, create a self-reinforcing downward spiral. Collective action by leaders can arrest the spiral, though the speed and effectiveness which they act ultimately determines the length and severity of the crisis."

My own reaction is similar, except for some different emphasis and a slightly different slant, based on extensive readings about other panics and crashes, including a first hand look at the tech bubble collapse of 2001.

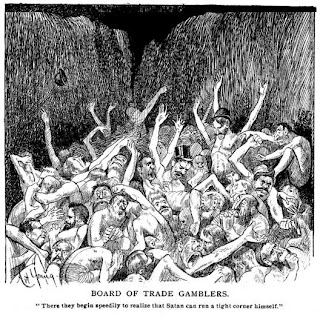

First, almost all panics and crashes are preceded by sustained periods of artificial growth, not based on improvements in productivity, but by a false expansion in the money system, aided and abetted by speculators and financiers. Although they do not act in overt cooperation, yet there is an unmistakable collusion of purpose. It suggests that the impulse to benefit in this way is present in a portion of the people at all times, as there are impulses to do many other things for personal benefit without regard to the public good. But at certain times the prohibitions which normally hold this behaviour in check are weakened, sometimes through active interventions against regulation, at other times from a decline in moral conscience.

Seocnd, almost all panics and crashes involves relatively small groups of people who seem to be at the heart of the matter, and are closely interlinked into small cartels of corrupted self-dealing involving the accumulation of enormous personal fortunes. One is struck by the interconnectedness of the primary players in the Panic of 1907 in each others companies, banks, investments, and boards of directors.

In this instance there did not seem to be any significant corruption of the government, which was actually in a progressive mood under Theodore Roosevelt, although he was by now a lame duck. Rather, the central government at this time was weak, and regulation was largely in the hands of the business principals, of which no greater example than J. Pierpont Morgan. They will act to protect their own interests when threatened, but their benevolent reputations are greatly exaggerated.

Lastly, there is always the overextension of credit and excessive leverage. Always. This is how the Ponzi scheme grows, for that is in every case what precedes and precipitates the growth of a crisis and panic - the unreasonable overvaluation and expansion of assets concentrations provoked again by a relatively small number of men, interlinked loosely through business associations.

As in the case of 1907 and its aftermath, a few visible persons are offered up for punishment and destruction, but the largest and most substantial of the predators remain unscathed, often being lionized as saviours who attempted the rescue of the nation from a few bad apples and the public from its own folly.

Although the authors make a great deal of the need to take swift and decisive action to stem the crisis, they miss the point that the place to stop this is before the leverage and excess build to the point where almost anything will set the overextended system into crisis and panic. Even if decisive action is taken, it is the greater public that is invariably harmed by the cure, with a few becoming even more enriched, although the harm be less than if nothing had been done at all. By the time the crisis is underway, you will be making deals of convenience, and at terms with the devil.

It should be stressed that there is no evidence in the correspondence of any of the principals that they desired to cause this Panic of 1907 for their own benefit. And there does not have to be.

It should be stressed that there is no evidence in the correspondence of any of the principals that they desired to cause this Panic of 1907 for their own benefit. And there does not have to be. If a general atmosphere of looting is fostered by the provocations of a few like-minded individuals, their subsequent actions need no coordination, other than the insufficient response of society to stop them before they gain sufficient momentum from their desires. It is the apathy and weakness of the many that provides the stimulus and the encouragement for their plans.

The authors do recount the subsequent meeting of many of the principals at Jekyll Island in 1910, to craft a reform of the banking system to be known as The Federal Reserve System. Again, I do not see anything in the system itself that is improper or malignant; it is only in it ability to increase and amplify leverage that makes it a powerful tool in like-minded individuals to seek to defraud the many of their life savings through unscrupulous abuse of anything and everything that comes under their power and control.

If you wish to take the measure of a society, look to how its weakest members are protected from its strongest, and its predators skulking at the fringes.

More concisely, you will receive the results that you incent, the behaviours that you cultivate, the society that you promote, if only by doing nothing and allowing small groups of like-minded individuals to set your greater agenda. We have seen this repeatedly in companies both large and small, in entire industries, and we think in the national economy.

If you wish a hell on earth, do nothing for the benefit of others, for the greater good, or to inhibit those who act solely out of greed, fear, and hate. Soon enough you will have a society that is intensely self-interested, self-concerned, superficial, destructive and self-consuming.

A free and just society is not a prize to be won or a gift that can be bestowed; it is a recurring commitment, and an enduring obligation.