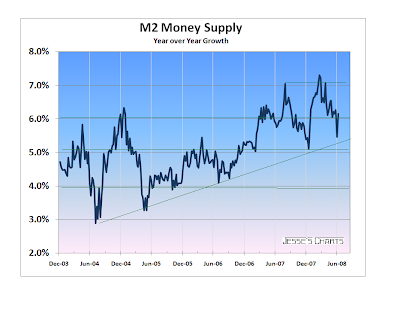

There is certainly a contraction in the growth of bank credit and the money supply.

Please note that these are reductions in growth, and from some recently lofty heights.

Before this is over, we ought to see some contraction in the overall supply of money. This is what we had seen in 2002 as the market approached bottom.

One question rarely considered by non-monetary economists is "What is the equilibrium rate of monetary growth, and is it always the same?"

If the economic population is not increasing, and the growth of real GDP is zero, should the money supply be increasing? If the economic population and real GDP are decreasing, would the correct level of monetary growth be a decrease to maintain stable prices? And then there is the matter of the velocity of money, and the notion of a virtual or derivative money supply. All good questions worthy of serious thought.

21 July 2008

Bank Credit and Money Supply Update

After Many a Summer Dies the Swan

The dollar decays, the dollar decays and falls,

The banks writedown their assets to the ground,

Bernanke comes and tills the field and lies beneath,

And after many a summer dies the swan.

with apologies to Alred Lord Tennyson, Tithonus

Here is an exposition of the view that we are heading into a Second Great Depression. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard lays out the facts well and makes some fine distinctions about the role of currencies, especially the dollar. This is critical in understanding events as they unfold.

We are not so certain that this is the correct path of events. Its aids us in making the case as to why a monetary deflation is a much less likely outcome for the US than it was for Japan. But this is certainly a scenario worth watching.

The global economy is at the point of maximum danger

Sunday, July 20, 2008

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

UK Telegraph

It feels like the summer of 1931. The world's two biggest financial institutions have had a heart attack. The global currency system is breaking down. The policy doctrines that got us into this mess are bankrupt. No world leader seems able to discern the problem, let alone forge a solution. (They know what the problem is, and also the solution. They are afraid to be the first to reveal the truth for fear of backlash, pressure from The Interests, and the blame for causing the bust when the abyss opens - Jesse)

The International Monetary Fund has abdicated into schizophrenia. It has upgraded its 2008 world forecast from 3.7 percent to 4.1 percent growth, whilst warning of a "chance of a global recession." Plainly, the IMF cannot or will not offer any useful insights. (Will not. - Jesse)

Its "mean-reversion" model misses the entire point of this crisis, which is that central banks have pushed debt to fatal levels by holding interest too low for a generation, and now the chickens have come home to roost. True "mean-reversion" would imply debt deflation on such a scale that would, if abrupt, threaten democracy. (Its more a matter of imbalance than degree we think, which is the dirty little secret. The vested Interests would rather a deflation or inflation than a redistribution of their ill-gotten gains to something more equitable. Better the lord of hell than a servant in heaven and all that. - Jesse)

The risk is that these same central banks will commit a fresh error, this time overreacting to the oil spike. The European Central Bank has raised rates, warning of a 1970s wage-price spiral. Fixated on the rear-view mirror, it is not looking through the windscreen.

The eurozone is falling into recession before the US itself. Its level of credit stress is worse, if measured by Euribor or the iTraxx bond indexes. Core inflation has fallen over the last year from 1.9 to 1.8 percent.

The US may soon tip into a second leg of this crisis as the fiscal package runs out and Americans lose jobs in earnest. US bank credit has contracted for three months. Real US wages fell at almost 10 percent (annualised) over May and June. This is a ferocious squeeze for an economy already in the grip of the property and debt crunch.

No doubt the rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac -- $5.3 trillion pillars of America's mortgage market -- stinks of moral hazard. The Treasury is to buy shares: the Fed has opened its window yet wider. Risks have been socialised. Any rewards will go to capitalists.

Alas, no Scandinavian discipline for Wall Street. When Norway's banks fell below critical capital levels in the early 1990s, the Storting authorised seizure. Shareholders were stiffed. (This is closer to what ought to have been done in the US - Jesse)

But Nordic purism in the vast universe of US credit would court fate. The Californian lender IndyMac was indeed seized after depositors panicked on the streets of Encino. The police had to restore order. This was America's Northern Rock moment.

IndyMac will deplete a tenth of the $53 billion reserve of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The FDIC has some 90 "troubled" lenders on watch. IndyMac was not one of them.

The awful reality is that Washington has its back to the wall. Fed chief Ben Bernanke thought the US could always get out of trouble by monetary stimulus "a l'outrance," and letting the dollar slide. He has learned that the world is a more complicated place. (Ben is just playing for time, trying to get lucky and avoid sharp objects and the blame for this - Jesse)

Oil has queered the pitch. So has America's fatal reliance on foreign debt. The Fannie/Freddie rescue, incidentally, has just lifted the US national debt from German AAA levels to Italian AA- levels. (At the end of the day the US dollar as global reserve currency is a Ponzi scheme, along with everything that it underpins. No one wishes to face this. Its down to a jockeying for power into the next phase. - Jesse)

China, Russia, petro-powers, and other foreign states own $985 billion of US agency debt, besides holdings of US Treasuries. Purchases of Fannie/Freddie debt covered a third of the US current account deficit of $700 billion over the last year. Alex Patelis from Merrill Lynch says America faces the risk of a "financing crisis" within months. Foreigners have a veto over US policy.

Japan did not have this problem during its Lost Decade. As the world's supplier of credit, it could let the yen slide. It also had a savings rate of 15 percent. Albert Edwards from Societe Generale says this has fallen to 3 percent today. It has cushioned the slump. Americans are under water before they start. (And this is why a monetary deflation is not a viable policy option for the US. We wish more people would 'get' this, and the fact that with a fiat currency with no pegs it is just a choice of policy. - Jesse)

My view is that a dollar crash will be averted as it becomes clearer that contagion has spread worldwide. But we are now at the point of maximum danger. Britain, Japan, and the Antipodes are stalling. Denmark is in recession. Germany contracted in the second quarter. May industrial output fell 6 percent in Holland and 5.5 percent in Sweden. (This is the view that we all go down together, and that some are quicker to rise again than others. Think 1930's. - Jesse)

The coalitions in Belgium and Austria have just collapsed. Germany's left-right team is fraying. One German banker told me that the doctrines of "left Nazism" (Otto Strasser's group, purged by Hitler) had captured the rising Die Linke party. The Social Democrats are picking up its themes to protect their flank.

This is the healthy part of Europe. Further south, we are not far away from civic protest. BNP Paribas has just issued a hurricane alert for Spain.

Finance minister Pedro Solbes said Spain is facing the "most complex" economic crisis in its history. Actually, it is very simple. The country was lulled into a trap by giveaway interest rates of 2 percent under EMU, leading to a current account deficit of 10 percent of GDP.

A manic property bubble was funded by foreigners buying covered bonds and securities. This market has dried up. Monetary policy is now being tightened into the crunch by the ECB, hence the bankruptcy last week of Martinsa-Fadesa (E5.1 billion). With Franco-era labour markets (70 percent of wages are inflation-linked), the adjustment will occur through closure of the job marts.

China, India, east Europe, and emerging Asia have all stolen growth from the future by condoning credit excess. To varying degrees, they are now being forced to pay back their own "inter-temporal overdrafts."

If we are lucky, America will start to stabilise before Asia goes down. Should our leaders mismanage affairs, almost every part of the global system will go down together. Then we are in trouble. (This is 'The Second Great Depression" scenario. - Jesse)

20 July 2008

The American Mainstream Media Says "Buy the Financials and Banks"

Good bottom call or siren song for a sucker's rally?

Good bottom call or siren song for a sucker's rally?

We think its the latter. Right now the banks, especially the investment banks, are obtaining a balance sheet smokescreen cover from the New York Fed.

In the short term we are going to lay off the short side on the financials and watch what happens, looking for a place to jump back on that trade. We won't fight the Fed, but we are not drinking the Kool-Aid either.

Why not buy the financials, just for a trade? It might work. We'd rather buy gold and play our gold-oil cross trade.

The next downdraft, when it comes, is likely to be breath-taking.

What to Bank On - Barron's

Hopes and Hints that Financial Stocks Have Finally Touched Bottom - New York Times

Jitters Ease as Citi, Rivals Show Signs of Bottoming Out - Wall Street Journal

19 July 2008

Why No Outrage? Remember, Remember, the Fourth of November

Many, many years ago a much younger Jesse had a wise old Boss from whom he learned many things about managing people and a piece of a larger business.

Many, many years ago a much younger Jesse had a wise old Boss from whom he learned many things about managing people and a piece of a larger business.

One day The Boss remarked in passing that he did not care when his guys were complaining about small things. He considered it healthy. "Its when they get quiet for a long time that you need to worry. That's that's a sign that something is fundamentally wrong in the company. And when the right spark comes along, all hell is going to break loose."

One slight difference we might have with Mr. Grant is that he seems US-centric in his thoughts. Keep an eye on Europe, specifically Britain. They may show the way ahead.

The American elections will be Tuesday 4 November 2008. Vote.

Why No Outrage?

By JAMES GRANT

July 19, 2008

The Wall Street Journal

Through history, outrageous financial behavior has been met with outrage. But today Wall Street's damaging recklessness has been met with near-silence, from a too-tolerant populace, argues James Grant

"Raise less corn and more hell," Mary Elizabeth Lease harangued Kansas farmers during America's Populist era, but no such voice cries out today. America's 21st-century financial victims make no protest against the Federal Reserve's policy of showering dollars on the people who would seem to need them least.

Long ago and far away, a brilliant man of letters floated an idea. To stop a financial panic cold, he proposed, a central bank should lend freely, though at a high rate of interest. Nonsense, countered a certain hard-headed commercial banker. Such a policy would only instigate more crises by egging on lenders and borrowers to take more risks. The commercial banker wrote clumsily, the man of letters fluently. It was no contest. (Lend free, but at a HIGH rate of interest makes perfect sense, then and now. It prevent an artificial seizure of a credit crunch, but also avoids bubbles and other unintended consequences of excessively cheap credit that fosters distortions. This is the hallmark of the Greenspan Fed, and it is carrying over into the Bernanke Fed. - Jesse)

The doctrine of activist central banking owes much to its progenitor, the Victorian genius Walter Bagehot. But Bagehot might not recognize his own idea in practice today. Late in the spring of 2007, American banks paid an average of 4.35% on three-month certificates of deposit. Then came the mortgage mess, and the Fed's crash program of interest-rate therapy. Today, a three-month CD yields just 2.65%, or little more than half the measured rate of inflation. It wasn't the nation's small savers who brought down Bear Stearns, or tried to fob off subprime mortgages as "triple-A." Yet it's the savers who took a pay cut -- and the savers who, today, in the heat of a presidential election year, are holding their tongues.

Possibly, there aren't enough thrifty voters in the 50 states to constitute a respectable quorum. But what about the rest of us, the uncounted improvident? Have we, too, not suffered at the hands of what used to be called The Interests? Have the stewards of other people's money not made a hash of high finance? Did they not enrich themselves in boom times, only to pass the cup to us, the taxpayers, in the bust? Where is the people's wrath?

The American people are famously slow to anger, but they are outdoing themselves in long suffering today. In the wake of the "greatest failure of ratings and risk management ever," to quote the considered judgment of the mortgage-research department of UBS, Wall Street wears a political bullseye. Yet the politicians take no pot shots. (They are afraid. They have been co-opted. They need to go and find some honest work. - Jesse)

Barack Obama, the silver-tongued herald of change, forgettably told a crowd in Madison, Wis., some months back, that he will "listen to Main Street, not just to Wall Street." John McCain, the angrier of the two presumptive presidential contenders, has staked out a principled position against greed and obscene profits but has gone no further to call the errant bankers and brokers to account.

The most blistering attack on the ancient target of American populism was served up last October by the then president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, William Poole. "We are going to take it out of the hides of Wall Street," muttered Mr. Poole into an open microphone, apparently much to his own chagrin. (The country is like an sullen mob, waiting for someone to make the first move - Jesse)

If by "we," Mr. Poole meant his employer, he was off the mark, for the Fed has burnished Wall Street's hide more than skinned it. The shareholders of Bear Stearns were ruined, it's true, but Wall Street called the loss a bargain in view of the risks that an insolvent Bear would have presented to the derivatives-laced financial system. To facilitate the rescue of that system, the Fed has sacrificed the quality of its own balance sheet. In June 2007, Treasury securities constituted 92% of the Fed's earning assets. Nowadays, they amount to just 54%. In their place are, among other things, loans to the nation's banks and brokerage firms, the very institutions whose share prices have been in a tailspin. Such lending has risen from no part of the Fed's assets on the eve of the crisis to 22% today. Once upon a time, economists taught that a currency draws its strength from the balance sheet of the central bank that issues it. I expect that this doctrine, which went out with the gold standard, will have its day again.

Wall Street is off the political agenda in 2008 for reasons we may only guess about. Possibly, in this time of widespread public participation in the stock market, "Wall Street" is really "Main Street." Or maybe Wall Street, its old self, owns both major political parties and their candidates. (and the mainstream media - Jesse) Or, possibly, the $4.50 gasoline price has absorbed every available erg of populist anger, or -- yet another possibility -- today's financial failures are too complex to stick in everyman's craw.

I have another theory, and that is that the old populists actually won. This is their financial system. They had demanded paper money, federally insured bank deposits and a heavy governmental hand in the distribution of credit, and now they have them. The Populist Party might have lost the elections in the hard times of the 1890s. But it won the future.

Before the Great Depression of the 1930s, there was the Great Depression of the 1880s and 1890s. Then the price level sagged and the value of the gold-backed dollar increased. Debts denominated in dollars likewise appreciated. Historians still debate the source of deflation of that era, but human progress seems the likeliest culprit. Advances in communication, transportation and productive technology had made the world a cornucopia. Abundance drove down prices, hurting some but helping many others.

The winners and losers conducted a spirited debate about the character of the dollar and the nature of the monetary system. "We want the abolition of the national banks, and we want the power to make loans direct from the government," Mary Lease -- "Mary Yellin" to her fans -- said. "We want the accursed foreclosure system wiped out.... We will stand by our homes and stay by our firesides by force if necessary, and we will not pay our debts to the loan-shark companies until the government pays its debts to us."

By and by, the lefties carried the day. They got their government-controlled money (the Federal Reserve opened for business in 1914), and their government-directed credit (Fannie Mae and the Federal Home Loan Banks were creatures of Great Depression No. 2; Freddie Mac came along in 1970). In 1971, they got their pure paper dollar. So today, the Fed can print all the dollars it deems expedient and the unwell federal mortgage giants, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, combine for $1.5 trillion in on-balance sheet mortgage assets and dominate the business of mortgage origination (in the fourth quarter of last year, private lenders garnered all of a 19% market share).

Thus, the Wall Street of the Morgans and the Astors and the bloated bondholders is today an institution of the mixed economy. It is hand-in-glove with the government, while the government is, of course -- in theory -- by and for the people. But that does not quite explain the lack of popular anger at the well-paid people who seem not to be very good at their jobs. ("The Interests" have a broader level of control thanks to the digital age and this hedonistic, dumbed-down generation than ever before. But their day to fall is coming. - Jesse)

Since the credit crisis burst out into the open in June 2007, inflation has risen and economic growth has faltered. The dollar exchange rate has weakened, the unemployment rate has increased and commodity prices have soared. The gold price, that running straw poll of the world's confidence in paper money, has jumped. House prices have dropped, mortgage foreclosures spiked and share prices of America's biggest financial institutions tumbled. One might infer from the lack of popular anger that the credit crisis was God's fault rather than the doing of the bankers and the rating agencies and the government's snoozing watchdogs. And though greed and error bear much of the blame, so, once more, does human progress. At the turn of the 21st century, just as at the close of the 19th, the global supply curve prosperously shifted. Hundreds of millions of new hands and minds made the world a cornucopia again. And, once again, prices tended to weaken. This time around, however, the Fed intervened to prop them up. In 2002 and 2003, Ben S. Bernanke, then a Fed governor under Chairman Alan Greenspan, led a campaign to make dollars more plentiful. The object, he said, was to forestall any tendency toward what Wal-Mart shoppers call everyday low prices. Rather, the Fed would engineer a decent minimum of inflation.

One might infer from the lack of popular anger that the credit crisis was God's fault rather than the doing of the bankers and the rating agencies and the government's snoozing watchdogs. And though greed and error bear much of the blame, so, once more, does human progress. At the turn of the 21st century, just as at the close of the 19th, the global supply curve prosperously shifted. Hundreds of millions of new hands and minds made the world a cornucopia again. And, once again, prices tended to weaken. This time around, however, the Fed intervened to prop them up. In 2002 and 2003, Ben S. Bernanke, then a Fed governor under Chairman Alan Greenspan, led a campaign to make dollars more plentiful. The object, he said, was to forestall any tendency toward what Wal-Mart shoppers call everyday low prices. Rather, the Fed would engineer a decent minimum of inflation.

In that vein, the central bank pushed the interest rate it controls, the so-called federal funds rate, all the way down to 1% and held it there for the 12 months ended June 2004. House prices levitated as mortgage underwriting standards collapsed. The credit markets went into speculative orbit, and an idea took hold. Risk, the bankers and brokers and professional investors decided, was yesteryear's problem.

Now began one of the wildest chapters in the history of lending and borrowing. In flush times, our financiers seemingly compete to do the craziest deal. They borrow to the eyes and pay themselves lordly bonuses. Naturally -- eventually -- they drive themselves, and the economy, into a crisis. And to the scene of this inevitable accident rush the government's first responders -- the Fed, the Treasury or the government-sponsored enterprises -- bearing the people's money. One might suppose that such a recurrent chain of blunders would gall a politically potent segment of the population. That it has evidently failed to do so in 2008 may be the only important unreported fact of this otherwise compulsively documented election season.

Mary Yellin would spit blood at the catalogue of the misdeeds of 21st-century Wall Street: the willful pretended ignorance over the triple-A ratings lavished on the flimsy contraptions of structured mortgage finance; the subsequent foreclosure blight; the refusal of Wall Street to honor its implied obligations to the holders of hundreds of billions of dollars worth of auction-rate securities, the auctions of which have stopped in their tracks; the government's attempt to prohibit short sales of the guilty institutions; and -- not least -- Wall Street's reckless love affair with heavy borrowing.

For every dollar of equity capital, a well-financed regional bank holds perhaps $10 in loans or securities. Wall Street's biggest broker-dealers could hardly bear to look themselves in the mirror if they didn't extend themselves three times further. At the end of 2007, Goldman Sachs had $26 of assets for every dollar of equity. Merrill Lynch had $32, Bear Stearns $34, Morgan Stanley $33 and Lehman Brothers $31. On average, then, about $3 in equity capital per $100 of assets. "Leverage," as the laying-on of debt is known in the trade, is the Hamburger Helper of finance. It makes a little capital go a long way, often much farther than it safely should. Managing balance sheets as highly leveraged as Wall Street's requires a keen eye and superb judgment. The rub is that human beings err.

Wall Street is usually described as an industry, but it shares precious few characteristics with the metal-fasteners business or the auto-parts trade. The big brokerage firms are not in business so much to make a product or even to earn a competitive return for their stockholders. Rather, they open their doors to pay their employees -- specifically, to maximize employee compensation in the short run. How best to do that? Why, to bear more risk by taking on more leverage.

"Wall Street is our bad example because it is so successful," charged the president of Notre Dame University, the Rev. John Cavanaugh, in the time of Mary Lease. He meant that young people, emulating J.P. Morgan or E.H. Harriman, would worship the wrong god. The more immediate risk today is that Wall Street, sweating to fill out this year's bonus pool, runs itself and the rest of the American financial system right over a cliff.

It's just happened, in fact, under the studiously averted gaze of the Street's risk managers. Today's bear market in financial assets is as nothing compared to the preceding crash in human judgment. Never was a disaster better advertised than the one now washing over us. House prices stopped going up in 2005, and cracks in mortgage credit started appearing in 2006. Yet the big, ostensibly sophisticated banks only pushed harder. Bear Stearns is kaput and Lehman Brothers is reeling, but Morgan Stanley perhaps best illustrates the gluttonous ways of Wall Street. Having lost its competitive edge on account of an intramural political struggle, the firm, under Chief Executive John Mack, set out to catch up to the rest of the pack. In the spring of 2006, it unveiled a trillion-dollar balance sheet, Wall Street's first. It expanded in every faddish business line, not excluding, in August 2006, subprime-mortgage origination (the transaction, intoned a Morgan Stanley press release, "provides us with new origination capabilities in the non-prime market, which we can build upon to provide access to high-quality product flows across all market cycles"). Nor did it pull in its horns as the boom wore on but rather protruded them all the more, raising its ratio of assets to equity to the aforementioned 33 times at year-end 2007 from 26.5 times at the close of 2004. Naturally, it did not forget the help. Last year, Morgan Stanley paid out 59% of its revenues in employee compensation, up from 46% in 2004.

Bear Stearns is kaput and Lehman Brothers is reeling, but Morgan Stanley perhaps best illustrates the gluttonous ways of Wall Street. Having lost its competitive edge on account of an intramural political struggle, the firm, under Chief Executive John Mack, set out to catch up to the rest of the pack. In the spring of 2006, it unveiled a trillion-dollar balance sheet, Wall Street's first. It expanded in every faddish business line, not excluding, in August 2006, subprime-mortgage origination (the transaction, intoned a Morgan Stanley press release, "provides us with new origination capabilities in the non-prime market, which we can build upon to provide access to high-quality product flows across all market cycles"). Nor did it pull in its horns as the boom wore on but rather protruded them all the more, raising its ratio of assets to equity to the aforementioned 33 times at year-end 2007 from 26.5 times at the close of 2004. Naturally, it did not forget the help. Last year, Morgan Stanley paid out 59% of its revenues in employee compensation, up from 46% in 2004.

Huey Long, who rhetorically picked up where Lease left off, once compared John D. Rockefeller to the fat guy who ruins a good barbecue by taking too much. Wall Street habitually takes too much. It would not be so bad if the inevitable bout of indigestion were its alone to bear. The trouble is that, in a world so heavily leveraged as this one, we all get a stomach ache. Not that anyone seems to be complaining this election season.

James Grant is the editor of Grant's Interest Rate Observer.