NY Times

NY Times

Fortress, the Hedge Fund, Is Crumbling

By MICHAEL J. DE LA MERCED

December 4, 2008

When Wesley R. Edens and his partners founded their investment firm a decade ago, they chose a name that evoked unshakeable bastions: Fortress.

But now their stronghold is under siege — and some of its investors are running for cover.

Cracks are spreading throughout the Fortress Investment Group, once a leading player in the worlds of hedge funds and leveraged buyouts. On Wednesday, Fortress’s shares fell 25 percent to $1.87, a new low, after the company temporarily suspended withdrawals from its largest hedge fund. Investors had asked to withdraw $3.51 billion from the money-losing fund, Drawbridge Global Macro.

But Wednesday’s slide was just the latest turn in a long, downward spiral for Fortress. The once-celebrated company has lost 89 percent of its market value over the last year as hedge funds and private equity, once lucrative businesses that helped define an era of unrivaled Wall Street wealth, have crumbled in the credit crisis.

It is a remarkable turnabout for Fortress, which less than two years ago was soaring along with the rest of Wall Street. Its debut as a public company, in February 2007, was heralded as the dawn of a new age of big hedge funds and buyout firms. Mr. Edens, a former executive at Lehman Brothers and BlackRock, and his fellow founders became instant billionaires. Their deal paved the way for even splashier initial public offerings by the likes of the Blackstone Group.

But life as public companies has proved treacherous for Fortress, Blackstone and the other so-called alternative investment firms that sold stock to the public shortly before the credit crisis erupted. They have had to contend with the harsh judgment of stockholders as the credit on which they depend has grown increasingly scarce.

“Frankly, it’s very difficult to say anything other than that I would have no interest as an investor in holding or buying these shares,” Jackson Turner, an analyst at Argus Research, said. Mr. Turner has a sell rating on Fortress shares.

A Fortress spokeswoman declined to comment.

Fortress’s plight reflects the ills plaguing much of high finance. Investors are abandoning hedge funds in growing numbers, and the industry, once so profitable, is now in the midst of a wrenching shakeout.

Even before Fortress lowered the gates on redemptions at its Drawbridge Global Macro fund, other big-name hedge funds had done so. More are expected to follow suit. Some investors fear that a rush of withdrawals could force funds to dump investments en masse, unsettling already shaky financial markets.

Fortress’s biggest fund is withering. In a regulatory filing on Wednesday, Fortress said that Drawbridge Global would have about $3.7 billion in assets under management as of Jan. 1, compared to the $8 billion it reported having as of Sept. 30.

But while Fortress’s earnings will suffer because of the redemptions — hedge funds earn fees based on both the amount of assets they manage and the performance of those funds — the withdrawals alone do not necessarily spell the company’s doom. Less than 30 percent of Fortress’s $34 billion in assets under management are subject to investor redemptions. Most are locked up in private equity funds that do not allow quick withdrawals of capital.

Still, private equity firms have been hurt by the near-freeze in the credit markets, which has limited their ability to strike new deals and dealt a severe blow to many of the debt-laden companies they own.

Fortress dodged a major setback when it managed to refinance IntraWest, the big Canadian ski resort. But investors worry that Fortress has taken damage from its exposure to the commercial real estate market, which is coming under severe stress. Fortress was a major lender to Harry Macklowe, the real estate mogul, who had to sell off trophy properties like the General Motors Building in Manhattan to pay back his creditors.

Just as it was the first major alternative-investment manager to go public, Fortress is now being watched closely as a canary in the coal mine. The Drawbridge fund’s nearly 50 percent redemption rate far outpaces the 20 to 30 percent that the market had expected at hedge funds on average, said Roger Freeman, an analyst at Barclays Capital.

“From my standpoint, I wonder how many other funds are seeing similar redemption rates,” he said. “This is definitely a negative indicator for the industry.”

For months, Fortress has been the subject of gallows humor suggesting that it might simply buy back its shares and take itself private once more. While the company’s executives have asserted their commitment to remaining public, several analysts said that Fortress’s problems were clearly intensified by the brighter light that comes with being a public company.

“It forces their problems to be out in the open,” Mr. Turner said. “It made the issues that they have much more amplified.”

04 December 2008

Credit Crisis Storms the Walls of Fortress the Hedge Fund

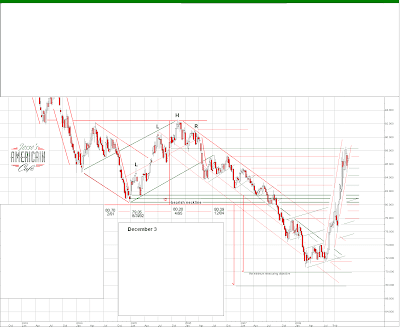

03 December 2008

Legg Mason's Bill Miller Calls 'the Bottom'

Presumably this is a different bottom than the one he called in April 2008.

Presumably this is a different bottom than the one he called in April 2008.

"The worst is behind us." 23 April 2008 - Bill Miller

Bill Miller of Legg Mason Calls a Bottom

Reuters

Legg Mason's Miller: "Bottom's been made" in stocks

By Jennifer Ablan and Herbert Lash

Wed Dec 3, 2008 3:56pm EST

NEW YORK, Dec 3 (Reuters) - Legg Mason's Bill Miller, a celebrated investor but whose stock picking is far off the mark this year, said on Wednesday the "bottom has been made" in U.S. equities.

He recommends that the Federal Reserve buy stocks and junk bonds to avert a deeper financial crisis, adding "the taxpayer would make a killing" as markets rebound. (Yikes! - Jesse)

Speaking at Legg Mason's annual luncheon for media, Miller said that all long-term investors believe that stocks today are cheap, but credit markets must regain health before equity markets can rally.

It "looks as if the bottom has been made" in U.S. stocks, he said.

Miller told Reuters the year has been "terrible, a disaster and awful," yet he held out his past performance in down markets as a reason why he should not be counted out.

"We've performed in most of the financial panics that we've had -- the last one being the three-year bear market ending in 2002 -- we outperformed all the way through that," he said.

"So even though we lost money, we lost a lot less money than the market did," Miller added.

However, Miller acknowledged that his performance has been worse than in past downturns.

For the year, Miller's flagship Value Trust LMVTX.O fund was down 59.7 percent as of Tuesday, compared to a 41 percent decline in the reinvested returns of the S&P 500 index, according to Lipper Inc., a unit of Thomson Reuters.

Performance over the year-to-date, one-, three- and five-year periods for Value Trust put it at the bottom of the barrel among its peers, Lipper data shows.

The severe sell-off has provided ample opportunities. (Yes. Like a plague creates plenty of vacancies in hotels - Jesse)

"This market is very unusual because since the end of the second quarter, it has been a pure scramble for liquidity which accelerated obviously post-Lehman Brothers and people sold without regard to value at all," Miller said.

"So at the end of the end of this quarter, every sector in the market has companies that represent what we think are exceptional value."