03 June 2013

NAV Premiums of Certain Precious Metal Trusts and Funds - Chasing Madoff, Chasing Metals

"The dissenter is every human being at those moments of his life when he resigns momentarily from the herd and thinks for himself."

Archibald Macleish

I had the opportunity to watch the documentary Chasing Madoff yesterday.

It is largely about how Harry Markopolos and his two associates discovered the likelihood of fraud in the Madoff fund, and their decade long battle to bring that fraud to light.

I do recommend you see it if you can.

What is most important, what everyone seems to be missing, is that Bernie Madoff was not some mad genius acting in secrecy through his cleverness. The dodgy nature of his fund was known by many hundreds of firms on the Street, and most anyone with a decent level of financial sophistication could readily see that something was wrong with his business model and returns.

Indeed, one could not see his scheme for the most part by willfully not looking at it, which is the course that the SEC took.

The scheme 'worked' for so long because Madoff let his enablers, the Street and the feeder funds, take the bulk of the fees from unwitting investors. So quite a few of the people who should have known were caught in a credibility trap. To expose Madoff would involve some risk for themselves, and to say nothing and plead ignorance was lucrative.

As for the media, Markopolos had written and gift-wrapped the story, made a list of witnesses, and mailed it to the Wall Street Journal years before the scheme was exposed. And it was killed from above. It wasn't until Madoff publicly confessed that the media responded, and then it was with spectacle rather than insight.

As for the SEC, although a few people were forced to resign, not one person involved was prosecuted. As has recently come out from a determined whistle-blower little mentioned in the press, it was a top down policy decision not to pursue any corruption in the investment management industry that caused the SEC to ignore this vast criminal conspiracy during the first decade of 2000.

And the irony is that even the work of Harry Markopolos did not lead to Madoff's downfall. The market panic in 2007 caused a run for liquidity, and at that point Madoff's scheme fell apart of its own weight. Madoff himself was able to plan his own confession, and make whatever provisions he wished beforehand as far as records and evidence.

In court he 'copped a plea' and was sentenced to 150 years, but did not speak, did not implicate anyone else.

There is a strong suggestion that very powerful and well connected people were involved in this, and that if he had taken some other course of action, Madoff would have been a dead man. This occurred before as the documentary shows, including the silencing of witnesses.

The plutocrats would like us to think that Madoff was just a clever rogue trader, some outsider. That the SEC were just lawyers incompetent in finance. That the press was too preoccupied with other things to investigate. And Markopolos was an obsessive oddball who happened to get it right. What happened was an anomaly. The system is secure.

This documentary reminded me very much of the precious metals market, although as a global market it is on a much grander scale. If so, I think that there is a good possibility that things will play out in the same way. Do I think this is some tortured analogy? Do you think that prices falling in the face of rising demand, stubborn secrecy, and numbers that never add up over a long period of time make sense? Good luck with that.

The regulators will keep stonewalling. The scheme to sell paper gold and silver, essentially the same bullion many times over, will go on until some event forces a run on supply, and then the scheme will collapse. It is both embarrassing and lucrative. It is all carrot and little stick. And so frauds like this can continue on for a long, long time.

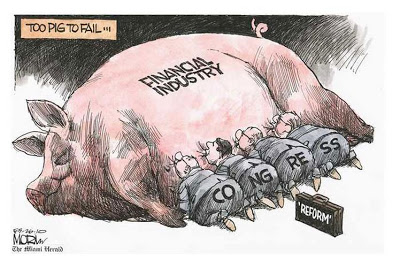

I think we should remember that despite all the histrionics in the Congress, and the fine talk of reform from the new president Obama, little to nothing has changed in the US financial industry. The same environment of compliant conspiracy to gain huge sums of easy money through a pathological criminality exists today. There are few investigations and even fewer prosecutions.

I think we have had our wake up calls several times, in the collapse of MF Global and what followed, the widespread rigging of the key LIBOR interest rate, and most recently in the odd market divergences between paper and reality. It is hard to believe these things when they happen, unless you understand what lies underneath them.

Take this for what it is worth. As the story Chasing Madoff says, because you see figures on a piece of paper, that does not necessarily mean that there is anything behind them. And when the scheme unravels, events move quickly. And many people are ruined, and no one seems to care.

Their hypocrisy knows no bounds, their willingness to hide the truth no limit. They do it to protect themselves, and 'the system' that serves them. One has to wonder how far it can go, and what happens when it can't.

There is a sad story in Chasing Madoff about a smart young man named Abe, whose father-in-law had a huge sum of money with the Madoff fund. Harry Markopolos handed over the evidence to him, and he showed it to his father-in-law. After the Madoff scandal became public, Abe called Harry Markopolos' associate and thanked him for what he did. He lost everything, because despite the evidence, his father-in-law could not believe that there could be a lie so huge for so long, and that Bernie, whom he had known for years, would cheat him.

I do think that the precious metals markets and a good part of the banking system today are such a scheme. And when something happens to break such a scheme, prices will adjust rather suddenly. I do expect a profound cover-up and a declaration of force majeure on some pretext.

There may even be some move to make people do something that they do not wish to do, such as hand over their metal in storage, which is not there anyway, or bail-in their bank deposits, or turn in their dollars for new dollars, at a rate of about 100 to 1. Or just take a big loss and shut up. Or something even harder to imagine. What limits are there to madness?

And then we will see what happens next. But I do not believe for one minute that this is over. To the contrary, I think we have only just begun. There will be no sustainable recovery without significant reform. Whether it is austerity or stimulus makes little difference when you are caught in a Ponzi scheme, and living a lie. There is no other option than increased transparency and reform.

Whatever wealth is provided goes to the top, and to continue to support the scheme. And the urge from the plutocrats and their enablers will be to silence the dissenters, and lash out at the weak, at the defenseless, and finally at the other. And if taken, history shows, almost without fail, that this is a Faustian bargain, a mariage de convenance with evil. And that madness serves only itself.

"I believe we have a crisis of values that is extremely deep, because the regulations and the legal structured need reform. But I meet a lot of these people on Wall Street on a regular basis right now. I'm going to put it very bluntly. I regard the moral environment as pathological. And I'm talking about the human interactions that I have. I've not seen anything like this, not felt it so palpably.

These people are out to make billions of dollars and nothing should stop them from that. They have no responsibility to pay taxes, they have no responsibility to their clients, they have no responsibility to people... counterparties in transactions. They are tough, greedy, aggressive, and feel absolutely out of control, in a quite literal sense. And they have gamed the system to a remarkable extent and they have a docile president, a docile White House and a docile regulatory system that absolutely can't find its voice. It's terrified of these companies.

If you look at the campaign contributions, which I happened to do yesterday for another purpose, the financial markets are the number one campaign contributors in the U.S. system now. We have a corrupt politics to the core, I'm afraid to say... both parties are up to their necks in this.

... But what it's led to is this sense of impunity that is really stunning and you feel it on the individual level right now. And it's very, very unhealthy. I have waited for four years... five years now to see one figure on Wall Street speak in a moral language. And I've have not seen it once. And that is shocking to me. And if they won't, I've waited for a judge, for our president, for somebody, and it hasn't happened. And by the way it's not going to happen any time soon, it seems.

Jeffrey Sachs

Category:

financial corruption,

Madoff,

Madoff fraud,

ponzi scheme,

regulatory capture

02 June 2013

Ben Bernanke's Commencement Address at Princeton

There is nothing particularly earth shattering revealed here, just a few choice tidbits perhaps.

I just enjoyed this speech. I wish that Ben and his colleagues were better candidates for a new edition of profiles in courage, possessed a greater breadth of empathy for those whom their decisions effect, and understood the difference among technical knowledge, sentimentality, and real wisdom.

And I like the Princeton campus. I attended classes in Japanese language and culture for a couple years on Nassau Street as I recall. I also took my GMATs there in one of the classrooms, far too early on a Saturday morning, many years ago. There's a nice lunch place on the corner. It's a very pretty place.

Ben S. Bernanke speaking at the Baccalaureate Ceremony at Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

June 2, 2013

The Ten Suggestions

It's nice to be back at Princeton. I find it difficult to believe that it's been almost 11 years since I departed these halls for Washington. I wrote recently to inquire about the status of my leave from the university, and the letter I got back began, "Regrettably, Princeton receives many more qualified applicants for faculty positions than we can accommodate." (1)

I'll extend my best wishes to the seniors later, but first I want to congratulate the parents and families here. As a parent myself, I know that putting your kid through college these days is no walk in the park. Some years ago I had a colleague who sent three kids through Princeton even though neither he nor his wife attended this university. He and his spouse were very proud of that accomplishment, as they should have been. But my colleague also used to say that, from a financial perspective, the experience was like buying a new Cadillac every year and then driving it off a cliff. I should say that he always added that he would do it all over again in a minute. So, well done, moms, dads, and families.

This is indeed an impressive and appropriate setting for a commencement. I am sure that, from this lectern, any number of distinguished spiritual leaders have ruminated on the lessons of the Ten Commandments. I don't have that kind of confidence, and, anyway, coveting your neighbor's ox or donkey is not the problem it used to be, so I thought I would use my few minutes today to make Ten Suggestions, or maybe just Ten Observations, about the world and your lives after Princeton. Please note, these points have nothing whatsoever to do with interest rates. My qualification for making such suggestions, or observations, besides having kindly been invited to speak today by President Tilghman, is the same as the reason that your obnoxious brother or sister got to go to bed later--I am older than you. All of what follows has been road-tested in real-life situations, but past performance is no guarantee of future results.

1. The poet Robert Burns once said something about the best-laid plans of mice and men ganging aft agley, whatever "agley" means. A more contemporary philosopher, Forrest Gump, said something similar about life and boxes of chocolates and not knowing what you are going to get. They were both right. Life is amazingly unpredictable; any 22-year-old who thinks he or she knows where they will be in 10 years, much less in 30, is simply lacking imagination. Look what happened to me: A dozen years ago I was minding my own business teaching Economics 101 in Alexander Hall and trying to think of good excuses for avoiding faculty meetings. Then I got a phone call . . . In case you are skeptical of Forrest Gump's insight, here's a concrete suggestion for each of the graduating seniors. Take a few minutes the first chance you get and talk to an alum participating in his or her 25th, or 30th, or 40th reunion--you know, somebody who was near the front of the P-rade. Ask them, back when they were graduating 25, 30, or 40 years ago, where they expected to be today. If you can get them to open up, they will tell you that today they are happy and satisfied in various measures, or not, and their personal stories will be filled with highs and lows and in-betweens. But, I am willing to bet, those life stories will in almost all cases be quite different, in large and small ways, from what they expected when they started out. This is a good thing, not a bad thing; who wants to know the end of a story that's only in its early chapters? Don't be afraid to let the drama play out.

2. Does the fact that our lives are so influenced by chance and seemingly small decisions and actions mean that there is no point to planning, to striving? Not at all. Whatever life may have in store for you, each of you has a grand, lifelong project, and that is the development of yourself as a human being. Your family and friends and your time at Princeton have given you a good start. What will you do with it? Will you keep learning and thinking hard and critically about the most important questions? Will you become an emotionally stronger person, more generous, more loving, more ethical? Will you involve yourself actively and constructively in the world? Many things will happen in your lives, pleasant and not so pleasant, but, paraphrasing a Woodrow Wilson School adage from the time I was here, "Wherever you go, there you are." If you are not happy with yourself, even the loftiest achievements won't bring you much satisfaction.

3. The concept of success leads me to consider so-called meritocracies and their implications. We have been taught that meritocratic institutions and societies are fair. Putting aside the reality that no system, including our own, is really entirely meritocratic, meritocracies may be fairer and more efficient than some alternatives. But fair in an absolute sense? Think about it. A meritocracy is a system in which the people who are the luckiest in their health and genetic endowment; luckiest in terms of family support, encouragement, and, probably, income; luckiest in their educational and career opportunities; and luckiest in so many other ways difficult to enumerate--these are the folks who reap the largest rewards. The only way for even a putative meritocracy to hope to pass ethical muster, to be considered fair, is if those who are the luckiest in all of those respects also have the greatest responsibility to work hard, to contribute to the betterment of the world, and to share their luck with others. As the Gospel of Luke says (and I am sure my rabbi will forgive me for quoting the New Testament in a good cause): "From everyone to whom much has been given, much will be required; and from the one to whom much has been entrusted, even more will be demanded" (Luke 12:48, New Revised Standard Version Bible). Kind of grading on the curve, you might say.

4. Who is worthy of admiration? The admonition from Luke--which is shared by most ethical and philosophical traditions, by the way--helps with this question as well. Those most worthy of admiration are those who have made the best use of their advantages or, alternatively, coped most courageously with their adversities. I think most of us would agree that people who have, say, little formal schooling but labor honestly and diligently to help feed, clothe, and educate their families are deserving of greater respect--and help, if necessary--than many people who are superficially more successful. They're more fun to have a beer with, too. That's all that I know about sociology.

5. Since I have covered what I know about sociology, I might as well say something about political science as well. In regard to politics, I have always liked Lily Tomlin's line, in paraphrase: "I try to be cynical, but I just can't keep up." We all feel that way sometime. Actually, having been in Washington now for almost 11 years, as I mentioned, I feel that way quite a bit. Ultimately, though, cynicism is a poor substitute for critical thought and constructive action. Sure, interests and money and ideology all matter, as you learned in political science. But my experience is that most of our politicians and policymakers are trying to do the right thing, according to their own views and consciences, most of the time. If you think that the bad or indifferent results that too often come out of Washington are due to base motives and bad intentions, you are giving politicians and policymakers way too much credit for being effective. Honest error in the face of complex and possibly intractable problems is a far more important source of bad results than are bad motives. For these reasons, the greatest forces in Washington are ideas, and people prepared to act on those ideas. Public service isn't easy. But, in the end, if you are inclined in that direction, it is a worthy and challenging pursuit.

6. Having taken a stab at sociology and political science, let me wrap up economics while I'm at it. Economics is a highly sophisticated field of thought that is superb at explaining to policymakers precisely why the choices they made in the past were wrong. About the future, not so much. However, careful economic analysis does have one important benefit, which is that it can help kill ideas that are completely logically inconsistent or wildly at variance with the data. This insight covers at least 90 percent of proposed economic policies.

7. I'm not going to tell you that money doesn't matter, because you wouldn't believe me anyway. In fact, for too many people around the world, money is literally a life-or-death proposition. But if you are part of the lucky minority with the ability to choose, remember that money is a means, not an end. A career decision based only on money and not on love of the work or a desire to make a difference is a recipe for unhappiness.

8. Nobody likes to fail but failure is an essential part of life and of learning. If your uniform isn't dirty, you haven't been in the game.

9. I spoke earlier about definitions of personal success in an unpredictable world. I hope that as you develop your own definition of success, you will be able to do so, if you wish, with a close companion on your journey. In making that choice, remember that physical beauty is evolution's way of assuring us that the other person doesn't have too many intestinal parasites. Don't get me wrong, I am all for beauty, romance, and sexual attraction--where would Hollywood and Madison Avenue be without them? But while important, those are not the only things to look for in a partner. The two of you will have a long trip together, I hope, and you will need each other's support and sympathy more times than you can count. Speaking as somebody who has been happily married for 35 years, I can't imagine any choice more consequential for a lifelong journey than the choice of a traveling companion.

10. Call your mom and dad once in a while. A time will come when you will want your own grown-up, busy, hyper-successful children to call you. Also, remember who paid your tuition to Princeton.

Those are my suggestions. They're probably worth exactly what you paid for them. But they come from someone who shares your affection for this great institution and who wishes you the best for the future.

Congratulations, graduates. Give 'em hell.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Note to journalists: This is a joke. My leave from Princeton expired in 2005.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)