For the first time we had a 'jobless recovery' after the tech bubble bust thanks to the wonders of Greenspan's monetary expansion and the willingness (gullibility?) of the average American to assume enormous amounts of debt, largely based on home mortgages, the house as ATM phenomenon. Not to mention the large, unfunded expenditures of the government thanks to tax cuts and multiple wars.

Now the pundits are talking about the hopes for another jobless recovery.

Who is going to go deeply into debt this time? It looks like its the government's turn. And the expectation is that foreigners will continue to suck up the debt.

If you think this explosion of Federal debt will facilitate a stronger US dollar you might be suffering from ideological myopia or some other delusion.

Some years ago we forecast that the financiers and their elites would take the world down this road of leveraged debt and malinvestment, and then make you an offer that they think you cannot refuse. They will seek to frighten you with a collapse of the existing financial order, because that is what they fear the most themselves, for their own unique positions of power.

The offer will be a one world currency, which is a giant step towards a one world government, managed by them of course. Once you control the money, local fiscal and social preferences start to matter less and less.

This theory seems more plausible today than it did then.

28 October 2009

About The Jobless Recovery ....

19 January 2009

Some Thoughts on the Debt Disaster in the US and UK and Possible Alternatives

This is a rather important essay in that it nicely frames up the problem that we face, and the constraints on the remedies at our disposal.

This is a rather important essay in that it nicely frames up the problem that we face, and the constraints on the remedies at our disposal.

We will be speaking more about that in the near term, but for now here is a framework by which to understand the boundaries, the 'lay of the land.'

The key point is that the debt to GDP ratio has become unsustainable. The way to correct this is to lower it to a level that is manageable and to work it down.

It will likely require a combination of inflation and debt reduction by bankruptcies and writedowns in order to restore the economy to something which can be used to achieve a balance.

Liquidationism is a trap because it reduces GDP and cripples the productive economy as it reduces debt. It is similar to poisoning a patient to treat an infection. It is favored only by those who believe that they can insulate themselves and profit by it.

Without serious systemic reforms, any remedies will not obtain traction, merely provide a new step function for a repetition of the cycle of debt expansion, as was done in the series of credit bubbles under Alan Greenspan and Bush-Clinton.

The impact will be felt around the globe because of the interconnectedness of the world economy and finance, but the heart of the problem is in the US and the UK.

Economic Times

US and UK on brink of debt disaster

20 Jan, 2009, 0419 hrs IST

LONDON: The United States and the United Kingdom stand on the brink of the largest debt crisis in history.

While both governments experiment with quantitative easing, bad banks to absorb non-performing loans, and state guarantees to restart bank lending, the only real way out is some combination of widespread corporate default, debt write-downs and inflation to reduce the burden of debt to more manageable levels. Everything else is window-dressing. (Quantitative easing, bad banks, and state guarantees are the instruments of inflation. The amount of inflation that the West can manage will greatly affect the amount of these more draconian measures - Jesse)

To understand the scale of the problem, and why it leaves so few options for policymakers, which shows the growth in the real economy (measured by nominal GDP) and the financial sector (measured by total credit market instruments outstanding) since 1952.

In 1952, the United States was emerging from the Second World War and the conflict in Korea with a strong economy, and fairly low debt, split between a relatively large government debt (amounting to 68 percent of GDP) and a relatively small private sector one (just 60 percent of GDP).

Over the next 23 years, the volume of debt increased, but the rise was broadly in line with growth in the rest of the economy, so the overall ratio of total debts to GDP changed little, from 128 percent in 1952 to 155 percent in 1975.

The only real change was in the composition. Private debts increased (7.8 times) more rapidly than public ones (1.5 times). As a result, there was a marked shift in the debt stock from public debt (just 37 percent of GDP in 1975) toward private sector obligations (117 percent). But this was not unusual. It should be seen as a return to more normal patterns of debt issuance after the wartime period in which the government commandeered resources for the war effort and rationed borrowing by the private sector.

From the 1970s onward, however, the economy has undergone two profound structural shifts. First, the economy as a whole has become much more indebted. Output rose eight times between 1975 and 2007. But the total volume of debt rose a staggering 20 times, more than twice as fast. The total debt-to-GDP ratio surged from 155 percent to 355 percent.

Second, almost all this extra debt has come from the private sector. Despite acres of newsprint devoted to the federal budget deficit over the last thirty years, public debt at all levels has risen only 11.5 times since 1975. This is slightly faster than the eight-fold increase in nominal GDP over the same period, but government debt has still only risen from 37 percent of GDP to 52 percent.

Instead, the real debt explosion has come from the private sector. Private debt outstanding has risen an enormous 22 times, three times faster than the economy as a whole, and fast enough to take the ratio of private debt to GDP from 117 percent to 303 percent in a little over thirty years.

For the most part, policymakers have been comfortable with rising private debt levels. Officials have cited a wide range of reasons why the economy can safely operate with much higher levels of debt than before, including improvements in macroeconomic management that have muted the business cycle and led to lower inflation and interest rates. But there is a suspicion that tolerance for private rather than public sector debt simply reflected an ideological preference.

THE DEBT MOUNTAIN

The data makes clear the rise in private sector debt had become unsustainable. In the 1960s and 1970s, total debt was rising at roughly the same rate as nominal GDP. By 2000-2007, total debt was rising almost twice as fast as output, with the rapid issuance all coming from the private sector, as well as state and local governments.

This created a dangerous interdependence between GDP growth (which could only be sustained by massive borrowing and rapid increases in the volume of debt) and the debt stock (which could only be serviced if the economy continued its swift and uninterrupted expansion).

The resulting debt was only sustainable so long as economic conditions remained extremely favorable. The sheer volume of private-sector obligations the economy was carrying implied an increasing vulnerability to any shock that changed the terms on which financing was available, or altered the underlying GDP cash flows.

The proximate trigger of the debt crisis was the deterioration in lending standards and rise in default rates on subprime mortgage loans. But the widening divergence revealed in the charts suggests a crisis had become inevitable sooner or later. If not subprime lending, there would have been some other trigger.

WRONGHEADED POLICIES

The charts strongly suggest the necessary condition for resolving the debt crisis is a reduction in the outstanding volume of debt, an increase in nominal GDP, or some combination of the two, to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio to a more sustainable level.

From this perspective, it is clear many of the existing policies being pursued in the United States and the United Kingdom will not resolve the crisis because they do not lower the debt ratio.

In particular, having governments buy distressed assets from the banks, or provide loan guarantees, is not an effective solution. It does not reduce the volume of debt, or force recognition of losses. It merely re-denominates private sector obligations to be met by households and firms as public ones to be met by the taxpayer.

This type of debt swap would make sense if the problem was liquidity rather than solvency. But in current circumstances, taxpayers are being asked to shoulder some or all of the cost of defaults, rather than provide a temporarily liquidity bridge.

In some ways, government is better placed to absorb losses than individual banks and investors, because it can spread them across a larger base of taxpayers. But in the current crisis, the volume of debts that potentially need to be refinanced is so large it will stretch even the tax and debt-raising resources of the state, and risks crowding out other spending.

Trying to cut debt by reducing consumption and investment, lowering wages, boosting saving and paying down debt out of current income is unlikely to be effective either. The resulting retrenchment would lead to sharp falls in both real output and the price level, depressing nominal GDP. Government retrenchment simply intensified the depression during the early 1930s. Private sector retrenchment and wage cuts will do the same in the 2000s.

BANKRUPTCY OR INFLATION

The solution must be some combination of policies to reduce the level of debt or raise nominal GDP. The simplest way to reduce debt is through bankruptcy, in which some or all of debts are deemed unrecoverable and are simply extinguished, ceasing to exist.

Bankruptcy would ensure the cost of resolving the debt crisis falls where it belongs. Investor portfolios and pension funds would take a severe but one-time hit. Healthy businesses would survive, minus the encumbrance of debt.

But widespread bankruptcies are probably socially and politically unacceptable. The alternative is some mechanism for refinancing debt on terms which are more favorable to borrowers (replacing short term debt at higher rates with longer-dated paper at lower ones).

The final option is to raise nominal GDP so it becomes easier to finance debt payments from augmented cashflow. But counter-cyclical policies to sustain GDP will not be enough. Governments in both the United States and the United Kingdom need to raise nominal GDP and debt-service capacity, not simply sustain it.

There is not much government can do to accelerate the real rate of growth. The remaining option is to tolerate, even encourage, a faster rate of inflation to improve debt-service capacity. Even more than debt nationalization, inflation is the ultimate way to spread the costs of debt workout across the widest possible section of the population.

The need to work down real debt and boost cash flow provides the motive, while the massive liquidity injections into the financial system provide the means. The stage is set for a long period of slow growth as debts are worked down and a rise in inflation in the medium term.

18 January 2009

The Fed is Monetizing Debt and Inflating the Money Supply

Here are the latest figures on the growth of the various money supply measures.

Here are the latest figures on the growth of the various money supply measures.

See Money Supply: A Primer for a review of measures and their differences.

The charts indicate that the growth in the money supply is due to a significant monetization of debt by the Fed in expanding its balance sheet and deficit spending by the Treasury, rather than organic growth from credit expansion from commercial sources and economic activity. The negative GDP figures confirm this.

You could imagine this as a tug of war if you wish. On one side is the deflationary force of bad debt and falling aggregate demand. On the other is the Treasury, the Fed, and the Congress, using the triple threat of deficit spending, monetization of debt, and stimulus programs. The limits of the power of the Feds are the value of the dollar and the acceptability of Treasury debt.

There is no lack of debt that can be monetized. To think otherwise is fantasy. But there are limitations about how much the dollar can bear, which is why the banks and moneyed interests have shoved their way to the front of the line, and are gorging themselves now with a little help from their friends in the Treasury and the Fed. When the time comes they intend to throw the public agenda under the bus. Its an old script, many times performed with minor enhancements.

If the current trend continues, it will have an inflationary effect on certain financial assets and commodities, and a negative impact on the dollar. There are lags in the appearance of this, but it will come.

Because the Dollar Index (DX) is an outmoded and artificial measure of dollar strength, containing nothing to account for the Chinese renminbi for example, it may not be a true reflection of the progress of this inflation. Time will tell.

A similar case might be made for certain strategic commodities, gold and oil, which are the instrument of government policy. Although it is much less important, silver may be one of the first commodities to break out because the government maintains no significant physical inventory of it as it does for gold and oil.

The huge short interest in silver may be an ignored scandal on the order of the Madoff Ponzi fund, not in dollar magnitude, but likely in terms of regulatory lapse and deep capture.

M1 has become a much less useful measure of the money supply these days because of changes in banking rules and technology. However, M1 is a good intermediate measure of the impact of the growth in the Fed's balance sheet as it feeds through the system.

Growth in MZM frequently results in financial asset expansion once it gains traction.

The US Dollar does not generally react well to aggressive growth in MZM.

The growth of credit, organic growth from economic activity, is sluggish.

The growth in the Monetary Base due to Fed inflationary activity has been nothing short of spectacular, without equal in US monetary history. This makes all Money Multiplier measures that use the AMB in the denominator meaningless for now.

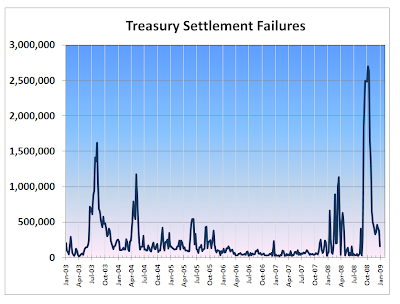

The spike in Treasury settlement failures is one measure of the stress in the financial system. It seems to be quieter now, after spiking in response to seizures in the bonds trading. We will maintain a watch on this.

15 January 2009

The Worst Is Yet to Come (But We Beat the Numbers) - J. P. Morgan

Interesting quotes from Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P. Morgan, the Fed's instrument of policy, their house bank, king of the derivatives pyramid, as the world is amazed that they beat the EPS numbers again this morning, at least on paper.

Interesting quotes from Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P. Morgan, the Fed's instrument of policy, their house bank, king of the derivatives pyramid, as the world is amazed that they beat the EPS numbers again this morning, at least on paper.

The problem is not so much the banking system and a lack of confidence in it. They do not deserve any. Our financial system has become a shell game, an extended accounting fraud, that permeates and selectively destroys whole segments of the real economy.

The problem is that the average consumer in the United States is a wage earner, and their real wages have been stagnating for the past twenty or more years, despite a rosier-than-reality set of CPI figures from the last two administrations.

The fact that most in New York and Washington have not quite realized yet is that the average American consumer is exhausted, tapped out, broke.

Providing easier credit terms, new sources of debt to feed the machine, may stretch this out a bit longer, may cushion the impact as the overloaded and imbalanced economy hits the wall, butit will do nothing to create sustainable growth.

Unless and until something is done to address the real median wage, to provide sources of income, rather than fresh sources of debt, to the middle class, there will be no recovery other than more monetary bubbles, that will be increasingly fragile and destructive in their collapse, ultimately testing the foundations of democracy.

The economic, and then the political, situation in the United States will deteriorate, perhaps much more rapidly than most would expect or even allow, unless something is done to break this cycle of debt and wealth transference, this illusion of vitality and stability.

AFP

JPMorgan chief says worst of the crisis still to come

Wed Jan 14, 10:13 pm ET

LONDON (AFP) – The chief executive of US bank JPMorgan Chase, Jamie Dimon, told the Financial Times on Thursday that the worst of the economic crisis still lay ahead as hard-hit consumers default on their loans.

"The worst of the economic situation is not yet behind us. It looks as if it will continue to deteriorate for most of 2009," he told the business daily.

"In terms of our sector, we expect consumer loans and credit cards to continue to get worse."

Dimon said the bank -- which bought rivals Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual last year -- was prepared for a deterioration in consumer-orientated businesses but if things were worse than expected, it would have to cut costs further.

The interview was published after a fresh wave of selling hit US and European stock markets Wednesday, as an unrelenting flow of bad economic and corporate news sparked fears of a deepening global downturn.

Bloomberg

JPMorgan Profit Drops 76 Percent, Less Than Analysts Estimated

By Elizabeth Hester

Jan. 15 (Bloomberg) -- JPMorgan Chase & Co., the second- largest U.S. bank by assets, said profit fell 76 percent, beating analysts’ estimates, as the company navigates the credit crisis with more success than most of its peers.

Fourth-quarter net income was $702 million, or 7 cents a share, compared with $2.97 billion, or 86 cents, a year earlier, the New York-based bank said today in a statement. Fourteen analysts surveyed by Bloomberg had an average earnings estimate of 1 cent a share.

JPMorgan’s $20.5 billion of writedowns, losses and credit provisions through the third quarter were less than a third of those at Citigroup Inc., which was forced to sell control of its Smith Barney brokerage to Morgan Stanley for $2.7 billion this week. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon has used JPMorgan’s relative strength to acquire troubled rivals, including Bear Stearns Cos. in March and Washington Mutual Inc. in September.

“JPM is better positioned against deteriorating loan portfolios than many of its peers given its strong loan-loss reserves,” KBW Inc. analyst David Konrad wrote in a Jan. 14 research note.

JPMorgan, which moved up its earnings announcement by six days, is the first of the largest U.S. banks to disclose fourth- quarter figures. New York-based Citigroup reports tomorrow, and Bank of America Corp., which bought Merrill Lynch & Co. two weeks ago, is scheduled to release results on Jan. 20. San Francisco- based Wells Fargo & Co. will follow on Jan. 28 as it works to absorb Wachovia Corp.

...Federal Reserve officials and President-elect Barack Obama have said more government help will be needed to shore up the U.S. financial system.

Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke said Jan. 13 that banks’ holdings of hard-to-sell investments raise questions about the companies’ underlying value, and called for the government to take on or insure the assets. Obama is deciding how to use the remaining $350 billion of the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program that Congress approved in October, with some Democrats saying the plan should favor homeowners and community banks over larger financial-services companies.

26 December 2008

Ponzi Nation

America has become more a debt 'junkie' - - than ever before

with total debt of $53 Trillion - - and the highest debt ratio in history.

That's $175,154 per man, woman and child - - or $700,616 per family of 4,

$33,781 more debt per family than last year.

Last year total debt increased $4.3 Trillion, 5.5 times more than GDP.

External debt owed foreign interests increased $2.2 Trillion;

Household, business and financial sector debt soared 7-11%.

80% ($42 trillion) of total debt was created since 1990,

a period primarily driven by debt instead of by productive activity.

And, the above does not include un-funded pensions and medical promises.

America's Total Debt Report - Grandfather's Economic Series

Since a picture is 'worth a 1000 words" here are a few charts for your consideration.

In a simple handwave estimate, one might say that the debt will have to be discounted by at least half. That includes inflation and selective defaults. The seductiveness of this chart is that things have continued on in their frenzied pace for so long, it seems like the norm. That is always a problem with chronic drunks and addicts; they rarely know when to quit, or can't, until they really hit the wall.

Nine out of ten Americans might understand that when the growth of your debt outrageously outstrips your income for so long, that something has got to give. The givers will most likely be all holders of US financial assets, responsible middle class savers, and a disproportionate share of foreign holders of US debt.

While the debtors hold the means of payment in dollars and the power to decide who gets paid, where do you think the most likely impact will be felt?

This is not intended as a rant, a screed in the pejorative sense, or anything else but a reasoned diagnosis based on the data as we find it.

We could be wrong, and we hope we are. Show us better data. The prognosis is not optimistic.

Here is a view of the debt data that is "optimistic" if you are willing to ignore the relative historic context and the huge amount of debts that are off the Federal balance sheet.

A dismissive reaction to this kind of forecast is understandable.

The doctor is always viewed as a 'party pooper' and a gloomy sort when he informs the uber-alpha hard drinking, stress generating, self-medicating, recreational drug=binging forty-something patient that their shortness of breath is emphysema, their blood pressure is soaring as quickly as their self-absorption, and that chest discomfort is a warning sign of a rapidly developing heart problem that could be a deal breaker if they do not change their lifestyle.

But, like most prognostic warnings go, it will be ignored with the dawn of a new day, a successful if awkward commute to work, and the anticipation of another evening's delight and binges yet to come. Until they don't.

It might be a good idea not to be a passenger with a recklessly self-destructive debt junkie at the wheel of your financial assets. Unless you are c0-dependent like Saudi Arabia, China and Japan or are one of the kids in the backseat. Then you have some serious decisions to make.

In the meantime buckle up, because Uncle Sugar-Daddy still has the keys to the car.

03 November 2008

The Next Bubble: Treasury Borrowing for Quarter to be $408 Billion More Than Expected

A tsunami of reserve currency debt issuance, coming soon to an economy near you.

Treasury expects to borrow record $550 billion

By Rex Nutting

3:00 p.m. EST Nov. 3, 2008

WASHINGTON -- The U.S. government is expected to borrow a record $550 billion in the current quarter, including $260 billion in special funding for the Federal Reserve's extraordinary liquidity programs, the Treasury Department said Monday.

The borrowing estimate is $408 billion more than estimated three months ago. For the first three months of 2009, the government is expected to borrow $368 billion, the government said.

In the three months ending September, the government borrowed $530 billion. The Treasury will announce on Wednesday the sizes and terms of its quarterly refunding auction.

AP

$900 billion in gov't borrowing seen through March

Goverment, raising cash for rescue, projects borrowing of more than $900 billion through March

November 03, 2008: 6:23 PM EST

NEW YORK (Associated Press) - The government, raising cash to pay for the array of financial rescue packages, said Monday it plans to borrow $550 billion in the last three months of this year --- and that's just a down payment.

Treasury Department officials also projected the government would need to borrow $368 billion more in the first three months of 2009, meaning the next president will confront an ocean of red ink.

The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Budget estimates all the government economic and rescue initiatives, starting with the $168 billion in stimulus checks issued earlier this year, total even more -- an eye-popping $2.6 trillion.

One day before voters set out to elect the 44th president, new economic reports brought more bad news...

In addition to the borrowing numbers, Treasury released estimates by major Wall Street bond firms projecting that total borrowing for this budget year, which began Oct. 1, will total $1.4 trillion, nearly double the previous record.

Major Wall Street firms were equally pessimistic about the size of the federal deficit this year. They projected it will hit $988 billion for the current budget year, more than twice the record. In July, the administration projected a deficit for this year of $482 billion, but that was before the financial crisis erupted in September.

Supporters of the government rescue packages argue that the ultimate cost to taxpayers should end up being a lot smaller, partly because the Federal Reserve is extending loans to banks that should be paid back.

And in the case of the $700 billion rescue package, the government is buying assets - either bank stock or distressed mortgage-backed assets _ that it hopes will rebound in value once the crisis has passed.

But the government still needs to borrow massive amounts to buy the assets, an effort that has driven up borrowing costs to levels never before contemplated....