This was no accident, no act of God. No unforeseen mishap, no simple miscalculation.

This was no accident, no act of God. No unforeseen mishap, no simple miscalculation.

Somebody pushed AIG out a window, to collect the insurance. Then they saw the opportunity to extort billions from the Congress and a Presidency in transition by bringing the financial system to the point of collapse. And they took it. And somebody knows who and how they did it.

Somebody knows.

NY Times

Goldman Helped Push A.I.G. to Precipice

By GRETCHEN MORGENSON and LOUISE STORY

February 6, 2010

...Well before the federal government bailed out A.I.G. in September 2008, Goldman’s demands for billions of dollars from the insurer helped put it in a precarious financial position by bleeding much-needed cash. That ultimately provoked the government to step in.

With taxpayer assistance to A.I.G. currently totaling $180 billion, regulatory and Congressional scrutiny of Goldman’s role in the insurer’s downfall is increasing. The Securities and Exchange Commission is examining the payment demands that a number of firms — most prominently Goldman — made during 2007 and 2008 as the mortgage market imploded.

The S.E.C. wants to know whether any of the demands improperly distressed the mortgage market, according to people briefed on the matter who requested anonymity because the inquiry was intended to be confidential. In just the year before the A.I.G. bailout, Goldman collected more than $7 billion from A.I.G. And Goldman received billions more after the rescue. Though other banks also benefited, Goldman received more taxpayer money, $12.9 billion, than any other firm.

In just the year before the A.I.G. bailout, Goldman collected more than $7 billion from A.I.G. And Goldman received billions more after the rescue. Though other banks also benefited, Goldman received more taxpayer money, $12.9 billion, than any other firm.

In addition, according to two people with knowledge of the positions, a portion of the $11 billion in taxpayer money that went to Société Générale, a French bank that traded with A.I.G., was subsequently transferred to Goldman under a deal the two banks had struck.

Goldman stood to gain from the housing market’s implosion because in late 2006, the firm had begun to make huge trades that would pay off if the mortgage market soured. The further mortgage securities’ prices fell, the greater were Goldman’s profits...

In its dispute with A.I.G., Goldman invariably argued that the securities in dispute were worth less than A.I.G. estimated — and in many cases, less than the prices at which other dealers valued the securities.

The pricing dispute, and Goldman’s bets that the housing market would decline, has left some questioning whether Goldman had other reasons for lowballing the value of the securities that A.I.G. had insured, said Bill Brown, a law professor at Duke University who is a former employee of both Goldman and A.I.G. The dispute between the two companies, he said, “was the tip of the iceberg of this whole crisis.”

The dispute between the two companies, he said, “was the tip of the iceberg of this whole crisis.”

“It’s not just who was right and who was wrong,” Mr. Brown said. “I also want to know their motivations. There could have been an incentive for Goldman to say, ‘A.I.G., you owe me more money.’ ”

Goldman is proud of its reputation for aggressively protecting itself and its shareholders from losses as it did in the dispute with A.I.G.

In March 2009, David A. Viniar, Goldman’s chief financial officer, discussed his firm’s dispute with A.I.G. in a conference call with reporters. “We believed that the value of these positions was lower than they believed,” he said.

Asked by a reporter whether his bank’s persistent payment demands had contributed to A.I.G.’s woes, Mr. Viniar said that Goldman had done nothing wrong and that the firm was merely seeking to enforce its insurance policy with A.I.G. “I don’t think there is any guilt whatsoever,” he concluded.

Lucas van Praag, a Goldman spokesman, reiterated that position. “We requested the collateral we were entitled to under the terms of our agreements,” he said in a written statement, “and the idea that A.I.G. collapsed because of our marks is ridiculous.” Still, documents show there were unusual aspects to the deals with Goldman. The bank resisted, for example, letting third parties value the securities as its contracts with A.I.G. required. And Goldman based some payment demands on lower-rated bonds that A.I.G.’s insurance did not even cover.

Still, documents show there were unusual aspects to the deals with Goldman. The bank resisted, for example, letting third parties value the securities as its contracts with A.I.G. required. And Goldman based some payment demands on lower-rated bonds that A.I.G.’s insurance did not even cover.

A November 2008 analysis by BlackRock, a leading asset management firm, noted that Goldman’s valuations of the securities that A.I.G. insured were “consistently lower than third-party prices.”

To be sure, many now agree that A.I.G. was reckless during the mortgage mania. The firm, once the world’s largest insurer, had written far more insurance than it could have possibly paid if a national mortgage debacle occurred — as, in fact, it did.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the relationship between Goldman and A.I.G. was that without the insurer to provide credit insurance, the investment bank could not have generated some of its enormous profits betting against the mortgage market. And when that market went south, A.I.G. became its biggest casualty — and Goldman became one of the biggest beneficiaries.

Longstanding Ties

For decades, A.I.G. and Goldman had a deep and mutually beneficial relationship, and at one point in the 1990s, they even considered merging. At around the same time, in 1998, A.I.G. entered a lucrative new business: insuring the least risky portions of corporate loans or other assets that were bundled into securities.

...Mr. Egol structured a group of deals — known as Abacus — so that Goldman could benefit from a housing collapse. Many of them were actually packages of A.I.G. insurance written against mortgage bonds, indicating that Mr. Egol and Goldman believed that A.I.G. would have to make large payments if the housing market ran aground. About $5.5 billion of Mr. Egol’s deals still sat on A.I.G.’s books when the insurer was bailed out. “Al probably did not know it, but he was working with the bears of Goldman,” a former Goldman salesman, who requested anonymity so he would not jeopardize his business relationships, said of Mr. Frost. “He was signing A.I.G. up to insure trades made by people with really very negative views” of the housing market.

“Al probably did not know it, but he was working with the bears of Goldman,” a former Goldman salesman, who requested anonymity so he would not jeopardize his business relationships, said of Mr. Frost. “He was signing A.I.G. up to insure trades made by people with really very negative views” of the housing market.

Mr. Sundaram’s trades represented another large part of Goldman’s business with A.I.G. According to five former Goldman employees, Mr. Sundaram used financing from other banks like Société Générale and Calyon to purchase less risky mortgage securities from competitors like Merrill Lynch and then insure the assets with A.I.G. — helping fatten the mortgage pipeline that would prove so harmful to Wall Street, investors and taxpayers. In October 2008, just after A.I.G. collapsed, Goldman made Mr. Sundaram a partner.

Through Société Générale, Goldman was also able to buy more insurance on mortgage securities from A.I.G., according to a former A.I.G. executive with direct knowledge of the deals. A spokesman for Société Générale declined to comment.

It is unclear how much Goldman bought through the French bank, but A.I.G. documents show that Goldman was involved in pricing half of Société Générale’s $18.6 billion in trades with A.I.G. and that the insurer’s executives believed that Goldman pressed Société Générale to also demand payments.

Goldman’s Tough Terms

In addition to insuring Mr. Sundaram’s and Mr. Egol’s trades with A.I.G., Goldman also negotiated aggressively with A.I.G. — often requiring the insurer to make payments when the value of mortgage bonds fell by just 4 percent. Most other banks dealing with A.I.G. did not receive payments until losses exceeded 8 percent, the insurer’s records show. Several former Goldman partners said it was not surprising that Goldman sought such tough terms, given the firm’s longstanding focus on risk management.

Several former Goldman partners said it was not surprising that Goldman sought such tough terms, given the firm’s longstanding focus on risk management.

By July 2007, when Goldman demanded its first payment from A.I.G. — $1.8 billion — the investment bank had already taken trading positions that would pay out if the mortgage market weakened, according to seven former Goldman employees.

Still, Goldman’s initial call surprised A.I.G. officials, according to three A.I.G. employees with direct knowledge of the situation. The insurer put up $450 million on Aug. 10, 2007, to appease Goldman, but A.I.G. remained resistant in the following months and, according to internal messages, was convinced that Goldman was also pushing other trading partners to ask A.I.G. for payments.

On Nov. 1, 2007, for example, an e-mail message from Mr. Cassano, the head of A.I.G. Financial Products, to Elias Habayeb, an A.I.G. accounting executive, said that a payment demand from Société Générale had been “spurred by GS calling them.”

Mr. Habayeb, who testified before Congress last month that the payment demands were a major contributor to A.I.G.’s downfall, declined to be interviewed and referred questions to A.I.G. The insurer also declined to comment for this article. Mr. van Praag, the Goldman spokesman, said Goldman did not push other firms to demand payments from AIG....

Read the entire story here.

06 February 2010

Rorschach's Journal: Last Night, a Comedian Died in New York...

Fortune Editor Suggests That the US Treasury Will Have to Start Defaulting On Its Bonds

Disclosure: The title of this blog entry is almost as sensationalistically misleading as the headline of the Fortune news article below.

Social Security is broke and will need a bailout, "even as the bank bailout is winding down" according to a Fortune story by Allan Sloan. Notice how cleverly the correlation is made between bank entitlements because of speculative excess and what is essentially the paid for portion of a retirement annuity invested solely in Treasury debt.

And bank bailout winding down? That is an illusion. Wall Street has placed its vampiric mouth into the heart of the monetary system, and has institutionalized its feeding. The bank bailout will be over when quantitative easing it over, the Treasury stops placing the public purse in guarantee of toxic assets, and the Fed stops monetizing the Treasuries.

Social Security is broke IF the Treasury defaults on all the bonds issued to the Social Security Administration, not only in its interest payments, but also by confiscating the trillions of underlying principal for which it has issued bonds.

It is broke IF you expect Social Security to act as a cash cow to subsidize other government spending, in a period of exceptionally low interest rates due to quantitative easing to subsidize the banks, and diminished tax income receipts because of a collapsing bubble created by the financial sector.

It is broke IF there is no economic recovery. Ever.

We are not talking about future payments. We are talking about the confiscation of taxes already received, and of Treasury bonds. Granted those Bonds are not traded publicly, but the principle is the same. It is about the full faith and confidence of the US government.

I am absolutely shocked that an editor of a major US financial publication would so blithely presume to suggest that Treasury debt is no good, and that the US can default, albeit selectively, at will. At the same time they promote a 'strong dollar' as the world's reserve currency out of the other sides of their mouth. Do they think we are idiots? It appears so.

If the Treasury does not honor its obligations, if America can treat its own people, its fathers and mothers, so shamefully, what would make one think it would not dishonour its obligations to them, should the need and opportunity arise?

The flip answer might be, "It's gone, the government has stolen the Social Security Fund already. Too bad for the old folks, no matter to me." Well, if that is the case, my friend, what makes you think there is any more substance to those Treasuries you are holding in your account, and those dollars in your pocket? What is backing them? Are they not traveling down the same path of quiet confiscation ad insolvency? People have a remarkable ability to kid themselves that someone else's misfortune will not be their own, even when they are in similar circumstances.

The US has not quite reached this point yet I think. But it may be coming. First they come for the weak.

Is this merely a play to resurrect the Bush proposal to channel the Social Security Funds to Wall Street? It seems as though it might be. Or merely another facet of a propaganda campaign to set Social Security up for more reductions besides fraudulent COLA adjustments as the financial sector crowds out even more of the real economy through acts of accounting theft and seignorage.

Let us remember that if the Social Security Fund is diverted from government obligations, the Treasury will be compelled to issue even more debt into the private markets to try and finance the general government obligations. The only difference will be that Wall Street will be able to extract more fees from a greater share of the economy. That is what this is all about, pure and simple. Fees and subsidies for the FIRE sector.

It should be kept in mind that Social Security payments feed almost directly into consumption, which is a key factor to GDP in a balanced economy.

What next? Commercials depicting old people as rats scurrying through the national pantry, feeding on the precious stores of the nation? How about the mentally and physically disabled? Aren't they a drain on SS as well? Better deal with them. Some blogs and chat boards are calling for a population reduction, and the shedding of undesirables, as defined by them. This Wall Street propaganda feeds that sort of ugliness. "It can't happen here" is as deadly an assumption as "It's different this time."

If this is what passes for economic thought and reporting, sponsored by a major mainstream media outlet from one of its editors, God help the United States of America. It has lost its mind, termporarily, but will likely lose its soul if it does not honour its oaths, especially that to uphold the Constitution against all threats, foreign and domestic.

Fortune

Next in Line for a Bailout: Social Security

by Allan Sloan

Thursday, February 4, 2010

Don't look now. But even as the bank bailout is winding down, another huge bailout is starting, this time for the Social Security system.

A report from the Congressional Budget Office shows that for the first time in 25 years, Social Security is taking in less in taxes than it is spending on benefits.

Instead of helping to finance the rest of the government, as it has done for decades, our nation's biggest social program needs help from the Treasury to keep benefit checks from bouncing -- in other words, a taxpayer bailout.

No one has officially announced that Social Security will be cash-negative this year. But you can figure it out for yourself, as I did, by comparing two numbers in the recent federal budget update that the nonpartisan CBO issued last week.

The first number is $120 billion, the interest that Social Security will earn on its trust fund in fiscal 2010 (see page 74 of the CBO report). The second is $92 billion, the overall Social Security surplus for fiscal 2010 (see page 116).

This means that without the interest income, Social Security will be $28 billion in the hole this fiscal year, which ends Sept. 30. (Lots of people and institutions are in trouble if you assume that the Treasury stops paying them interest income on the bonds which they have purchased, starting with the banks. And that income is already little enough because of the quantitative easing being conducted by the Fed to bail out the financial sector, which you represent at your magazine. - Jesse)

Why disregard the interest? Because as people like me have said repeatedly over the years, the interest, which consists of Treasury IOUs that the Social Security trust fund gets on its holdings of government securities, doesn't provide Social Security with any cash that it can use to pay its bills. The interest is merely an accounting entry with no economic significance. (You can say the same 'accounting entry' thing about any Treasury debt that is in excess of current tax receipts. And the Treasury doesn't provide any 'cash' to SS because it does not have to, it is probably the only major government program operating still at a surplus. Social Security payments do not go into the aether, they proceed almost directly into national consumption, which is GDP. - Jesse)

Social Security hasn't been cash-negative since the early 1980s, when it came so close to running out of money that it was making plans to stop sending out benefit checks. That led to the famous Greenspan Commission report, which recommended trimming benefits and raising taxes, which Congress did. Those actions produced hefty cash surpluses, which until this year have helped finance the rest of the government.

But even then, it was clear the surpluses would be temporary. Now, years earlier than projected, Social Security is adding to the government's borrowing needs, even though the program still shows a surplus on paper.

If you go to the aforementioned pages in the CBO update and consult the tables on them, you see that the budget office projects smaller cash deficits (about $19 billion annually) for fiscal 2011 and 2012. Then the program approaches break-even for a while before the deficits resume.

Social Security currently provides more than half the income for a majority of retirees. Given the declines in stock prices and home values that have whacked millions of people, the program seems likely to become more important in the future as a source of retirement income, rather than less important.

It would have been a lot simpler to fix the system years ago, when we could have used Social Security's cash surpluses to buy non-Treasury securities, such as government-backed mortgage bonds or high-grade corporates that would have helped cover future cash shortfalls. Now it's too late...

Read the rest here.

Volcker Rule: They Shoot Horses, Don't They?

If the Volcker Rule were posited as a panacea, much of the criticism that has been leveled by the bank lobbyists and their congressmen, and sincere critics who were surprised by its ungainly introduction into the reform deliberations, would be correct. However, I do not think it was, but I could be wrong.

If the Volcker Rule were posited as a panacea, much of the criticism that has been leveled by the bank lobbyists and their congressmen, and sincere critics who were surprised by its ungainly introduction into the reform deliberations, would be correct. However, I do not think it was, but I could be wrong.

Because a cure for heart disease does not also cure diabetes does not impugn its effectiveness in curing heart disease. And if the patient has both heart disease and diabetes, one might expect a variety of remedies used in careful combination.

What the Volcker Rule would have accomplished is to take the gamblers away from the new “discount window” of Fed and Treasury subsidized programs. It would have also put a serious dent in the ‘Too Big Too Fail’ meme, although it alone was not enough to do that, as it lacked some teeth. But it opened the door to a debate that is not occurring.

What exactly is the role of the financial system, and what needs to be done to regulate it, and help it to perform some utility to society's greater functions? Is the relationship between the financial sector and the productive economy out of balance?

I want to stress this. Any proposal that has not been hammered upon by multiple minds, and tempered with the objections and observations of many perspectives, is likely to be premature, needing much work. By its method of introduction, I fear that the reconsideration of the relationship between the FIRE sector and the productive economy is now off the table.

People seem to be making assumptions about what the Volcker Rule would and would not include. For example, there is reference to the 'shadow banking system' that is something relatively new, the intersection of investment banking and mortgage origination. Does anyone really believe that Volcker would object if mortgage origination and similar long term loans were relegated to the commercial banks and the GSE's? I think not.

For me, the 800 pound gorilla is who obtains access to the discount window and Treasury guarantee programs, and who can be a primary dealer for the Fed. I would say that a company that is not a bank cannot. It is as simple as that. And this is what Wall Street hates so much about anything like Glass-Steagall or the Volcker Rule. They want to be able to tap the Fed's balance sheet, and still maintain their aggressive leverage.

There is a reason that the banks engaged in a decades long effort, costing hundreds of millions in lobbying payments of various sorts, to overturn Glass-Steagall. To ignore that reality is to fall into the trap of the financial engineering distortion that is crippling the Western world. The bankers wanted to broaden their portfolio to intertwine their higher risk efforts with the public trust, as insurance against the occasional setback to even the best laid plans.

Relatively simple systems are more resilient and robust; needlessly complex systems are doomed to increase in complexity to the point of failure without accomplishing anything except more complexity.

The trade offs are always there, and a good system contains a mix of both.

Perhaps the new ‘reform legislation’ will be effective, but I doubt it quite a bit almost to the point of certainty. It will be hailed as an 'evolutionary effort' but will contain loopholes large enough to drive a CEO's bonus through. . If it does nothing to separate self interested, higher risk speculation from the trough of the Fed's balance sheet, it will institutionalize moral hazard, which has probably been the goal of the banks all along.

If the reform legislation relies on firms erecting 'chinese walls' within their firms, and regulators being able to sort out various types of regulated and unregulated activity within a firm, then it is my opinion that it is anathema to sound financial management, and doomed to failure. The problem is fraud, and deception, and regulatory capture. The rules must be as clear, simple, and difficult to cheat as is possible.

And then we will see the return of the financial pundits, suggesting this tweak, and that tweak, this addition to close that loophole, and if only we had made this change. Its a good game really, because it ensure a steady flow of funds from the bank lobby to the Congress, and full employment for financial engineers who can engage in endless argument about the relative merits of the latest tweak.

And the zombie banks will continue to drain the life from the real economy, not in dramatic bailouts, but in a steady stream of slow debilitation. But they will be able to pay enormous salaries and bonuses to their captains and lieutenants, by gaming nearly every financial instrument and market in the world.

This is what will doom the West to a stagflation that will mimic the long Japanese decline, their lost decades. It may not ultimately be resolved without social disorder.

The people are still too easily lulled by jargon and reassurance, and the econorati still believe in financial engineering. If only we put a clever tweak here, and an easy rule change there, things will be fine again. That is why allowing engineers to fix their own 'big system' problems is almost always doomed to failure, because they are too intellectually fascinated with their own creation, and cannot see it in the stark light of objectivity and its function as part of the whole.

How will we fix this? How will we accomplish that? Well, perhaps one can look at how those functions were addressed before the system started to go off kilter, say around 1990, and find an answer there. But that drives the financial engineering crew batty, because it sounds antithetical to Progress. It might stifle innovation.

Well, one might as well say that if they stop getting drunk and engaging in random sex, they will also not wake up next to so many new and interesting people. The point is, you do not have to engage in high risk behaviour to accomplish personal and institutional growth. And there is a role for stifling some things, so that only the good can thrive. It is a basic principle of what used to be called conservatism before it was co-opted by the neo-cons. We have to keep first principles in mind even as we change the specifics.

Was the real economy served better by subprime mortgage collateralization and the growth of an unregulated shadow banking system? Ask the average person, and the answer is clear. But the question is never put that way. To a financial engineer, it is the system itself that matters, and not its primary application, to serve the real economy. The objective of reform would ideally be more than merely preventing the next collapse of the same sort. It would involve giving the middle class a fighting chance to recover itself and prosper again. And that would involve shrinking the portfolio of the Wall Street banks, and expanding the function and stability or regional and local banking. Already the elite are softening up that hope, of a middle class recovery, by forecasting years of underemployment and decline as an inevitability.

The objective of reform would ideally be more than merely preventing the next collapse of the same sort. It would involve giving the middle class a fighting chance to recover itself and prosper again. And that would involve shrinking the portfolio of the Wall Street banks, and expanding the function and stability or regional and local banking. Already the elite are softening up that hope, of a middle class recovery, by forecasting years of underemployment and decline as an inevitability.

The title of this blog does not refer to the Volcker Rule, which was dead out of the gate by its method of introduction into the process, late and fleshless, and quite possibly by intent to stifle debate. It refers to the public, the poor horses that will be beaten senseless by the FIRE sector over the next ten years for their diversion and entertainment. Am I wrong?

So time to move on, to assess what will be coming out of Washington by way of reform. But I have little hope that there will be anything in it that does not serve about ten corporate institutions well, and a financial elite, to the disadvantage of the rest of the world in the form of distorted markets, institutionalized fraud, and the seignorage of the currency reserves.

Would that I am wrong, I doubt it very, very much.

05 February 2010

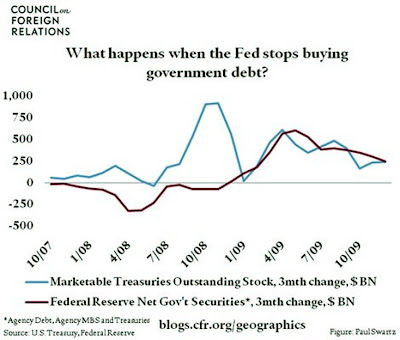

CFR: When the Fed Stops Monetizing US Sovereign Debt...

The people at the Council on Foreign Relations speculate that US interest rates on Treasury debt will be increasing around the end of the first quarter if the Fed discountinues its monetization of mortgage debt.

As the Fed has essentially purchased ALL new US Treasury issuance since 2009, that seems to be a reasonable bet.

"The Federal Reserve plans to stop buying securities issued by government housing loan agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by the end of the first quarter.

This is not only likely to push up mortgage rates; Treasury rates should rise as well. Throughout 2009, the private sector sold a portion of their agency holdings to the Fed and used those funds to buy Treasurys.

Once the Fed’s agency purchases stop, this private sector portfolio shift will end, removing a major source of demand in the Treasury market.

As the chart shows, since the start of 2009 the Fed has bought or financed the entire increase in Treasury issuance. As Fed purchases slow and Treasury issuance continues at a high level, interest rates will have to move up to attract new buyers."