There are several things of interest this week. The first and foremost is the Fed's FOMC two day meeting with their announcement on Wednesday at 2:15.

There are several things of interest this week. The first and foremost is the Fed's FOMC two day meeting with their announcement on Wednesday at 2:15.

It is important despite the fact that rates are effectively at zero, and the Fed has declared for 'quantitative easing.'

How does the Fed intend to implement this quantitative easing? Another way to ask this is to say, "What is the next bubble?"

Quantitative easing implies market distortion, and traders will be keen to understand where and how that distortion will play, because they are still geared for supercharged returns in an environment where fewer and fewer opportunities exist.

The Treasuries seem like a safer place, because lower interest rates are to the economy's benefit. Foreign entities may not like the monetization aspect, but we wonder how many real 'investors' are left in the bonds? Most in there are domestic parties seeking safe havens with any sort of return, and foreign central banks supporting political and industrial agendas.

So the focus will be on the wording of the Fed's statement once again, looking for clues with regard to the Fed's easing implementation and potential distortions that provide market inefficiencies.

Bloomberg

Bernanke Risks "Very Unstable" Markets as He Weighs Buying Bonds

By Rich Miller

January 25, 2009 19:01 EST

Jan. 26 (Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke and his colleagues may try once again to cure the aftermath of a bubble in one kind of asset by overheating the market for another.

Fed policy makers meeting tomorrow and the day after are exploring the purchase of longer-dated Treasury securities in an effort to push up their price and bring down their yield. Behind the potential move: a desire to reduce long-term borrowing costs at a time when the Fed can’t lower short-term interest rates any further because they are effectively at zero.

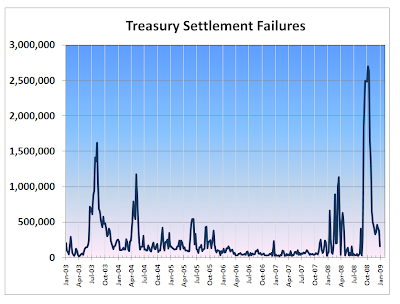

The risk is that central bankers will end up distorting the Treasury market, triggering wild swings in prices -- and long-term interest rates -- as investors react to what they say and do. “It sets forth a speculative dynamic that is very unstable,” says William Poole, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and now a senior fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington....

Inflated Prices

Recent history shows the economic danger of inflating asset prices. After a stock-market bubble burst in 2000, the Fed slashed interest rates to as low as 1 percent and in the process helped inflate the housing market. The collapse of that bubble is what eventually helped drive the U.S. into the current recession, the worst in a generation.

Faced with the danger of a deflationary decline in output, prices and wages, the Fed is considering steps to revive the moribund economy. On the table besides bond purchases: firming up a pledge to keep short-term interest rates low for an extended period and adopting some type of inflation target to underscore the Fed’s determination to avoid deflation.

The central bank has been buying long-term Treasury debt off and on for years as part of its day-to-day management of reserves in the banking system. Yet it has always gone out of its way to avoid influencing prices. What it’s discussing now, says former Fed Governor Laurence Meyer, is deliberately trying to push long rates below where they otherwise might be.

Fed Purchases

Bernanke raised this possibility in a speech on Dec. 1. While he didn’t specify what maturities the Fed might buy, in the past he has suggested that purchases might include securities with three- to six-year terms. (This is around the sweet spot for foreign Central Banks - Jesse)

Investors immediately took notice, with the yield on the 10-year note falling to 2.73 percent from 2.92 percent the day before. Yields fell further on Dec. 16, dropping to 2.26 percent from 2.51 percent the previous day, after the central bank’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee said it was studying the issue....

Yields have since risen, with the 10-year note ending last week at 2.62 percent. Behind the reversal: expectations of massive fresh supplies of Treasuries as the government is forced to finance an $825 billion economic-stimulus package and a possible new bank-bailout plan. This week alone, the Treasury is scheduled to auction $135 billion worth of securities.

Jump in Yields

David Rosenberg, chief North American economist for Merrill Lynch in New York, says the jump in yields may prompt the Fed to go ahead with Treasury purchases.

This isn’t the first time Bernanke and the Fed have discussed buying longer-dated securities and ended up roiling the market. Bernanke touted the idea as a tool to fight deflation in speeches in November 2002 and May 2003.

Egged on by his comments -- and later remarks by then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan that the central bank needed to build a “firewall” against deflation -- many investors became convinced the central bank was poised to buy bonds. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note fell to 3.11 percent in June 2003 from 3.81 percent at the start of the year.

Traders quickly reversed course as it became clear the Fed had no such intentions, sending the 10-year Treasury yield soaring to 4.6 percent just three months later, on Sept. 2.

‘Miscommunication’

Poole, who was then at the St. Louis Fed, was critical at the time of what he called the central bank’s “miscommunication.” He now sees the Fed making the same mistake with its latest suggestions that it might buy longer- dated securities.

“If they do it, it’s going to be disruptive to the market,” says Poole, who is a contributor to Bloomberg News. “If they don’t do it, it will impair the Fed’s credibility and erode the confidence the market has in the statements that the Fed makes.”

Meyer, now vice chairman of St. Louis-based Macroeconomic Advisers, says the Fed should, and probably will, go ahead with purchases as a way to lower borrowing costs. “The story is stop talking and start buying,” he says.

Still, he notes that not everyone at the Fed is enthusiastic about the idea. One concern: Foreign central banks and sovereign-wealth funds, which are big holders of Treasuries, might cool to buying many more if they believe prices are artificially high. (The buyers of our debt now are supporting their own industrial policy we would hope. Any other reason borders on mismanagement of funds while anyone in their country is hungry or unemployed - Jesse)

Undermine the Dollar

That may undermine the dollar. “There’s no guarantee that international investors would switch to other dollar- denominated debt if flushed from the Treasury market,” says Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP LLC in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Tony Crescenzi, chief bond-market strategist at Miller Tabak & Co. in New York, says foreign investors might also get spooked if they conclude that the Fed is monetizing the government’s debt -- in effect, printing money -- by buying Treasuries. (They already are, and they already are - Jesse)

Bernanke himself, in his 2003 speech, said monetization of the debt risked faster inflation -- something bond investors, foreign or domestic, wouldn’t like.

Some economists argue the Fed would help the economy more if it bought other types of debt. (Such as corporate bond - Jesse) Even after their recent rise, 10-year Treasury yields are still well below the 4.02 percent level at the start of last year....

Hawks at the Fed wouldn’t welcome such purchases. They are already uneasy that some of the central bank’s programs are effectively allocating credit to one part of the economy rather than others. Case in point: the Fed’s ongoing program to buy $500 billion of mortgage-backed securities, which Jeffrey Lacker, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, has called “credit policy” rather than monetary policy. (Its nice to see that someone else is noticing that the Fed has crossed the Rubicon from central bank to central economic planner in the worst sense of the description - Jesse)